Visit the MGH Division of Internal Medicine Healthy Lifestyle Program website to learn more about this webinars series and other initiatives.

|

Need some support with a health-oriented New Years resolution? Check out this webinar with Thrive Founder Katie Engels featuring strategies and tools to support sustainable behavior change.

Visit the MGH Division of Internal Medicine Healthy Lifestyle Program website to learn more about this webinars series and other initiatives. "Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk who was one of the world's most influential Zen masters, spreading messages of mindfulness, compassion and nonviolence, died on Saturday at his home in Tu Hieu Temple in Hue, Vietnam. He was 95." Read more about his life and legacy.

Watch Thrive Founder Katie Engels discuss her Health & Wellness Coaching Program at Mass General Hospital as part of the MGH Healthy Lifestyle Program’s “Think Outside the Pill” Stoeckle Center Seminar Presentation. As an introduction, she shared "it is so inspiring to be part of this team and today featured many opportunities to promote broader access to Health & Wellness Coaching throughout the Department of Internal Medicine."

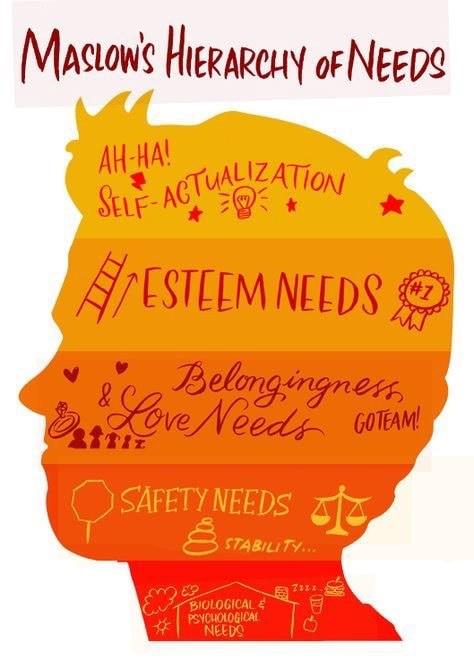

According to Beata Souders, MSPP, ACC, "when we replace giving directives and commands with working patiently and diligently to see the situation from the other person’s point of view, when we ask the other for input and suggestions, and when we then pull all that information together to offer some constructive goals and strategies, we often find that we tend to have better success in motivating others.

Daniel Pink, in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, explains why in today’s world extrinsic rewards do not work because most of us don’t perform rule-based routine tasks (2009). He argues, rather convincingly, that we need to create environments where intrinsic motivation thrives, where we can be creative and gain satisfaction from the activities themselves. If autonomy is our default setting, giving us a choice in terms of tasks, time, team, and technique is one way to increase it. When coupled with opportunities for growth and mastery, our intrinsic motivation increases through engagement. Pink tells us that mastery is a mindset, that it demands effort, and that it is like an asymptote where we get close to it but never fully realize it. He also reminds us of the importance of striving toward something greater than ourselves. Purpose, according to Pink, is not ornamental, but a vital source of aspiration and direction (2009)." Read more from the full article How to Motivate Someone, Including Yourself. Unwind this evening with this short guided mindfulness meditation And We Must Be Content With Stillness, featuring the Charles Tomlinson poem Farewell to Van Gogh.

Being mindful entails practicing being present and nonjudgemental, and when you commit to a regular mindfulness practice you strengthen your skills and ability to calm and center yourself in the face of life's challenges. Schedule a free thrive wellness coaching session to learn more about working with a wellness coach to develop a mindfulness practice. Farewell to Van Gogh The quiet deepens. You will not persuade One leaf of the accomplished, steady, darling Chestnut-tower to displace itself With more of violence than the air supplies When, gathering dusk, the pond brims evenly And we must be content with stillness. Unhastening, daylight withdraws from us its shapes Into their central calm. Stone by stone Your rhetoric is dispersed until the earth Becomes once more the earth, the leaves A sharp partition against cooling blue. Farewell, and for your instructive frenzy Gratitude. The world does not end tonight And the fruit that we shall pick tomorrow Await us, weighing the unstripped bough. Charles Tomlinson 1960 Have you noticed the disruption in the traditional dairy market due to consumer demand for plant-based alternative milks? The trend has emerged based on demand for plant-based options by those driven by health and wellness concerns, and it has been so pervasive, the dairy industry has (thus far unsuccessfully) lobbied to prevent plant-based milks to even call themselves "milks," reflecting the market share threat these products represent.

One of our greatest powers as individuals to cultivate the food system we want is to vote with our spending power on high-quality whole food plant-based foods and products. Vote for sustainable, organic, plant-centric eating with your spending habits. If you would like to shift your diet closer to a predominately whole food plant-based pattern, learn more about working with a thrive wellness coach to set medium- and short-term goals to support your change process. Take a 4 minute Mindfulness Break to calm and center yourself in the wake of stress.

Mindfulness skills gain power when you practice them regularly. Spend some time weekly on anything that pulls you into the present moment. This can be meditation, yoga, walking in nature, cooking, gardening, being active or even playing with young children. Spend some time each week on something that makes you lose track of time. When you commit to a regular mindfulness practice, you will have strengthened your ability to calm and center yourself, and this ability can be called on when you find yourself in an acutely stressful situation.  Dreaming of days when we can again take in the hum of the deep forest. Happy Earth Day from Thrive Wellness Coaching. Set the mood for some home yoga practice as you shelter with this 60 minute flow playlist, featuring mellow vibes, gradual wind down tunes from the peak pose to some supported last shapes, and chimes and rain at the end to frame your savasana.

Set up a free coaching session with a Thrive Wellness Coach to talk new year's resolutions for a better you in 2020.

According to Aldo Civico Ph.D., "matching and mirroring is the skill of assuming someone else’s style of behavior to create rapport. When you match and mirror, you don’t only listen with your ears, you listen with your entire body. You are present to the other person.

Matching and mirroring is not mimicry. To the contrary, it’s about being in tune with the other, by using your observations about the other’s behavior. Here are the four things you need to do, to match and mirror your interlocutor: Body postures and gestures What posture is the person you are having a conversation with assuming? What is he or she doing with his or her arms and hands? Is the person leaning forward or backward? Observe, and then match the posture and gestures. If, for example, the person is reserved in using the hands, there is no point for you to gesticulate frantically! The rhythm of the breath Pay attention to how the other person is breathing, and then match it. This technique helps tremendously in bonding with the other. If the person you are having a conversation with is breathing with her diaphragm, it will not help building rapport if you breath with your upper chest. Instead, match your interolocutor’s rhythm of breath. The energy level What is the energy level of your interlocutor? Is he or she shy, reserved or exuberant and extroverted? If he or she, for example, is timid, it might be perceived as aggressive and invasive if you are exuberant. If your interlocutor uses few words to express a concept, it does not make your communication effective if you are very wordy. The tone of your voice What is your interlocutor’s tone of voice? Is he or she talking softly, almost whispering? In that case, to build rapport, you need to mirror his or her tone of voice. Being loud, in fact, will not help establishing a bond with your interlocutor. In addition, pay attention at the speed of the speech. Is your interlocutor speaking slowly or fast? Paying attention to these four characteristics and mirroring them when communicating with others, helps you with rapport building (By the way, I am currently sending free videos to individuals interested in learning techniques on how to build rapport. Just sign up here for my weekly advice on effective communication). Read the full article here on Psychology Today. "Careers that rely primarily on fluid intelligence tend to peak early, while those that use more crystallized intelligence peak later," according to a recent Atlantic article.

British psychologist Raymond Cattell introduced the concepts of fluid and crystallized intelligence in the early 1940s. He defined fluid intelligence as "the ability to reason, analyze, and solve novel problems—what we commonly think of as raw intellectual horsepower." In contrast, crystallized intelligence "is the ability to use knowledge gained in the past, [like] possessing a vast library and understanding how to use it. It is the essence of wisdom." "Innovators typically have an abundance of fluid intelligence. It is highest relatively early in adulthood and diminishes starting in one’s 30s and 40s." Older people can find innovation more challenging. Crystallized intelligence is enhanced by "accumulating a stock of knowledge, and it "tends to increase through one’s 40s, and does not diminish until very late in life." This contrast is illustrated by two example careers. "Dean Keith Simonton has found that poets—highly fluid in their creativity—tend to have produced half their lifetime creative output by age 40 or so. Historians—who rely on a crystallized stock of knowledge—don’t reach this milestone until about 60." The good news is that "no matter what mix of intelligence your field requires, you can always endeavor to weight your career away from innovation and toward the strengths that persist, or even increase, later in life." For example, "teaching is an ability that decays very late in life, a principal exception to the general pattern of professional decline over time. A study in The Journal of Higher Education showed that the oldest college professors in disciplines requiring a large store of fixed knowledge, specifically the humanities, tended to get evaluated most positively by students. This probably explains the professional longevity of college professors, three-quarters of whom plan to retire after age 65—more than half of them after 70, and some 15 percent of them after 80. (The average American retires at 61.) One day, during my first year as a professor, I asked a colleague in his late 60s whether he’d ever considered retiring. He laughed, and told me he was more likely to leave his office horizontally than vertically." Are you craving a career change but don't know where to start? Work with a Thrive Wellness Coach to plan your next move. "Diet culture has made food and health a performance. Healing from diet culture and weight stigma means untangling from the performance and finding your way into a place where your needs, wants, desires and boundaries are louder than the externalized rules that demand adherence in exchange for worthiness."

From the Be Nourished Blog According to Sally Kempton, "We don’t always know why difficult people show up in our lives. There are some good theories about it, of course. Jungians, along with most contemporary spiritual teachers, tell us that ALL the people in our lives are mirroring what’s inside us, and that once we clear our minds and clarify our hearts; we’ll stop attracting angry girl friends, prickly co-workers and tyrannical bosses. Then there’s the view—not necessarily inconsistent with the first– that life is a school, and that difficult people are our teachers. (In fact, when someone tells you that you’re a teacher for him, it’s often a good idea to ask yourself exactly what it is about you that he finds abrasive!) One thing is clear, though: at some point in our lives, most of us will have someone around us who is show-stoppingly hard to take. Sometimes, it seems as if everyone we know is giving us trouble.

So, one of the great on-going questions for anyone who wants to live an authentic spiritual life without going into a cave is this: how do you deal with difficult people without being harsh, wimpy, or putting them out of your heart? How can you explain to your friend who keeps trying to enlist you in service of her own dramas, that you don’t want to be part of her latest scenario of mistrust and betrayal -- and still remain friends? How do you handle the boss whose tantrums terrorize the whole office, or the co-worker who bursts into tears several times a week and accuses you of being abrupt when all you’re trying to do is get down to business? More to the point, what can you do when the same sorts of difficult people and situations keep showing up again and again in your life? Should you chalk it up to karma? Should you find ways to resolve it through discussion or even pre-emptive action? Or should you take the truly challenging view that the people in your life who seem harsh or clingy or annoying are actually reflections of your own disowned, or shadow tendencies? In other words, is it really true that we project onto other people the qualities in ourselves that we dislike or disallow, and then condemn in someone else the traits we reject in ourselves? Does dealing with difficult people have to begin with finding out what you might need to work on in yourself? The short yogic answer here is "Yes." Obviously, that doesn’t mean you should overlook other people’s anti-social behavior. (Owning your own part in a difficult relationship is not the same thing as wimping out of a confrontation!) Moreover, some relationships are so difficult that the best way to change them is to leave. But here’s the bottom line: Try as we will, we can’t control other people’s personality and behavior. Our real power lies in our ability to work on ourselves. This, of course, is Yoga 101. We all ‘know’ it, yet when we’re in the crunch of relational malfunction, it’s often the first thing we forget. So, here it is again: your own inner state is your only platform for dealing successfully with other people. Not even the best interpersonal technique will work if you do it from a fearful, judgmental, or angry state of mind. Your own open and empowered state is the fulcrum, the power point, from which we can begin to move the world. [...] After all, what makes someone difficult? Essentially, it’s their energy. We don’t have to be students of quantum field theory or Buddhist metaphysics to sense how much the energies around us affect our moods and feelings. What makes someone tough for you to take? Basically, it has to do with how your energies interact with theirs. Every one of us is at our core an energetic bundle. What we call our personality is actually made up of many layers of energy -- soft, tender, vulnerable energies as well as powerful, controlling or prickly energies. We have our wild and gnarly energies, our kindly energies, our free energies and our constricted, contracted ones. These energies, expressing themselves through our bodies, thoughts, and emotions, and minds, manifest as our specific personality signature at any given moment. What we see on the surface, in someone’s body language and facial expressions, is the sum of the energies that are operating in them. As we speak, its the energy behind our words that most deeply impacts others. The beginning of change, then, is learning how to recognize and modulate our own energy patterns. The more awareness we have -- that is, the more we are able to stand aside and witness our personal energies of thought and feeling and (rather than identifying with them) "the easier it is to work with our own energies. This takes practice. Most people don’t start out with a highly developed awareness of their own energy or the way it impacts others -- and even fewer of us know how to change the way our energies work together." Sally Kempton is a student of Swami Muktananda, an author and a spiritual teacher. Excerpt above is from this article. "About 40 percent of people's daily activities are performed each day in almost the same situations, studies show. Habits emerge through associative learning. 'We find patterns of behavior that allow us to reach goals. We repeat what works, and when actions are repeated in a stable context, we form associations between cues and response,' a researcher explains.

Full Story Much of our daily lives are taken up by habits that we've formed over our lifetime. An important characteristic of a habit is that it's automatic-- we don't always recognize habits in our own behavior. Studies show that about 40 percent of people's daily activities are performed each day in almost the same situations. Habits emerge through associative learning. "We find patterns of behavior that allow us to reach goals. We repeat what works, and when actions are repeated in a stable context, we form associations between cues and response," Wendy Wood explains in her session at the American Psychological Association's 122nd Annual Convention. What are habits? Wood calls attention to the neurology of habits, and how they have a recognizable neural signature. When you are learning a response you engage your associative basal ganglia, which involves the prefrontal cortex and supports working memory so you can make decisions. As you repeat the behavior in the same context, the information is reorganized in your brain. It shifts to the sensory motor loop that supports representations of cue response associations, and no longer retains information on the goal or outcome. This shift from goal directed to context cue response helps to explain why our habits are rigid behaviors. There is a dual mind at play, Wood explains. When our intentional mind is engaged, we act in ways that meet an outcome we desire and typically we're aware of our intentions. Intentions can change quickly because we can make conscious decisions about what we want to do in the future that may be different from the past. However, when the habitual mind is engaged, our habits function largely outside of awareness. We can't easily articulate how we do our habits or why we do them, and they change slowly through repeated experience. "Our minds don't always integrate in the best way possible. Even when you know the right answer, you can't make yourself change the habitual behavior," Wood says. Participants in a study were asked to taste popcorn, and as expected, fresh popcorn was preferable to stale. But when participants were given popcorn in a movie theater, people who have a habit of eating popcorn at the movies ate just as much stale popcorn as participants in the fresh popcorn group. 'The thoughtful intentional mind is easily derailed and people tend to fall back on habitual behaviors. Forty percent of the time we're not thinking about what we're doing,' Wood interjects. 'Habits allow us to focus on other things…Willpower is a limited resource, and when it runs out you fall back on habits.' How can we change our habits? Public service announcements, educational programs, community workshops, and weight-loss programs are all geared toward improving your day-to-day habits. But are they really effective? These standard interventions are very successful at increasing motivation and desire. You will almost always leave feeling like you can change and that you want to change. The programs give you knowledge and goal-setting strategies for implementation, but these programs only address the intentional mind. In a study on the 'Take 5' program, 35 percent of people polled came away believing they should eat 5 fruits and vegetables a day. Looking at that result, it appears that the national program was effective at teaching people that it's important to have 5 servings of fruits and vegetables every day. But the data changes when you ask what people are actually eating. Only 11 percent of people reported that they met this goal. The program changed people's intentions, but it did not overrule habitual behavior. According to Wood, there are three main principles to consider when effectively changing habitual behavior. First, you must derail existing habits and create a window of opportunity to act on new intentions. Someone who moves to a new city or changes jobs has the perfect scenario to disrupt old cues and create new habits. When the cues for existing habits are removed, it's easier to form a new behavior. If you can't alter your entire environment by switching cities-- make small changes. For instance, if weight-loss or healthy eating is your goal, try moving unhealthy foods to a top shelf out of reach, or to the back of the freezer instead of in front. The second principle is remembering that repetition is key. Studies have shown it can take anywhere from 15 days to 254 days to truly form a new habit. 'There's no easy formula for how long it takes,' Wood says. Lastly, there must be stable context cues available in order to trigger a new pattern. "It's easier to maintain the behavior if it's repeated in a specific context," Wood emphasizes. Flossing after you brush your teeth allows the act of brushing to be the cue to remember to floss. Reversing the two behaviors is not as successful at creating a new flossing habit. Having an initial cue is a crucial component." Journal References 1. D. T. Neal, W. Wood, M. Wu, D. Kurlander. The Pull of the Past: When Do Habits Persist Despite Conflict With Motives? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2011; 37 (11): 1428 DOI: 10.1177/0146167211419863 2. Sarah Stark Casagrande, Youfa Wang, Cheryl Anderson, Tiffany L. Gary. Have Americans Increased Their Fruit and Vegetable Intake?The Trends Between 1988 and 2002. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2007; 32 (4): 257 DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.002 Source Society for Personality and Social Psychology. "How we form habits, change existing ones." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 8 August 2014. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140808111931.htm According to Andrew Cohen, “Ego is the deeply felt sense of being separate and superior. Indeed, it is an emotional and psychological compulsion to see and feel the self as being separate from and superior to the other, the world, and the whole universe. It is that locus point where the sense of individuality is also a sense of alienation, where the experience of autonomy is also one of isolation, and where even the experience of freedom is always shadowed, by a deeper sense, at the core of our being, by a sense of bondage, limitation, and hopelessness.

I believe that for most of us, the only solution to this evolutionary cul-de-sac, the only way to our own higher development, lies in the context of human relationship, relationship based upon a breakthrough to a shared experience and recognition of consciousness beyond ego -- a consciousness in which all parties experience simultaneously their own individual and collective transparency while remaining fully and completely themselves. In this higher We consciousness, we recognize, perhaps for the first time, why ego is the only problem, the only obstacle to the fulfillment of our imminent evolutionary potential. As long as the fears and desires of the ego remain the fundamental locus of our attention and the impulse to evolve is but a faint murmur in the background of awareness, nothing less than overwhelming force will bring the ego to its knees. The force of what? The force of impersonal absolute love that sees no other and recognizes only itself. In that love, our own higher conscience is awakened and screams relentlessly for our unconditional surrender without compromise. And it will keep on screaming until we all have finally transcended the need to be separate."  According to the VIA Institute on Character, "Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence is a strength that helps you connect with something outside yourself. It is about noticing the beauty all around you and feeling awe and appreciation for high-quality performance and work. It is a strength that can help you cope with emotional challenges or difficulties." Learn more about developing character strengths on the VIA Institute's website.  "Fame or integrity: which is more important? Money or happiness: which is more valuable? Success of failure: which is more destructive? If you look to others for fulfillment, you will never truly be fulfilled. If your happiness depends on money, you will never be happy with yourself. Be content with what you have; rejoice in the way things are. When you realize there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you." From chapter 44 of The Tao Te Ching written by Lao-Tau and translated by S. Mitchell  Mindfulness helps us put some space between ourselves and our reactions, breaking down our conditioned responses. Follow the steps below to begin your own mindfulness practice: 1. Set aside some time. You don’t need a meditation cushion or bench, or any sort of special equipment to access your mindfulness skills—but you do need to set aside some time and space. 2. Observe the present moment as it is. The aim of mindfulness is not quieting the mind, or attempting to achieve a state of eternal calm. The goal is simple: we’re aiming to pay attention to the present moment, without judgement. Easier said than done, we know. 3. Let your judgments roll by. When we notice judgements arise during our practice, we can make a mental note of them, and let them pass. 4. Return to observing the present moment as it is. Our minds often get carried away in thought. That’s why mindfulness is the practice of returning, again and again, to the present moment. 5. Be kind to your wandering mind. Don’t judge yourself for whatever thoughts crop up, just practice recognizing when your mind has wandered off, and gently bring it back. That’s the practice. It’s often been said that it’s very simple, but it’s not necessarily easy. The work is to just keep doing it, slowing impacting the way you think to attain greater peace. |

Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed